The History of Tattooing

Embellishing the skin with permanent tattoos is an ancient practice that can be traced back thousands of years and to many different cultures of the ancient world. Historically humans all over the world have been adorning their skin for a variety of reasons; to mark their social status, in religious rites, to beautify, for protection, to give themselves magical powers, to heal illnesses or to relieve pain. Often the body art was – and still is – used by various tribes in ignition rites, to mark coming of age or to commemorate other significant milestones in life.

The oldest known tattoos date back to the 4th millennium BC. In recorded history, the earliest tattoos can be found in Egypt during the time of the construction of the great pyramids. Their owners are Egyptian mummies, who, perhaps, can get into the Guinness Book of Records, as owners of the most durable tattoos.

In the nearly 24 years since he was discovered, Ötzi has provided a virtual treasure trove of information on the lives and times of Stone Age humans. He was discovered in 1991 by a pair of German hikers in the Otztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy. Mummified by the ebb and flow of glacial ice and discovered in the European Alps, the “Iceman” is the oldest intact human body ever found. He died around 3,500 B.C.

The researchers working on Ötzi recently announced that they have finished mapping out the mummy’s body art, finding 61 tattoos in total. The task proved tricky since the centuries have darkened his skin, obscuring the tattoos from the naked eye. To make them visible without damaging the body, the team of scientists used novel multispectral photographic imaging techniques. The tattoos mostly consist of parallel lines and x’s likely made by rubbing charcoal into purposely made cuts.

When the Egyptians expanded their empire, the art of tattooing spread as well. The civilizations of Crete, Greece, Persia, and Arabia picked up and expanded the art form. Around 2000 BC tattooing spread to China.

The Greeks used tattooing for communication among spies. Markings identified the spies and showed their rank. Romans marked criminals and slaves. This practice is still carried on today. The Ainu people of western Asia used tattooing to show social status. Girls coming of age were marked to announce their place in society, as were the married women. The Ainu are noted for introducing tattoos to Japan where it developed into a religious and ceremonial rite. In Borneo, women were the tattooists. It was a cultural tradition. They produced designs indicating the owner’s station in life and the tribe he belonged to. Kayan women had delicate arm tattoos which looked like lacy gloves. Dayak warriors who had “taken ahead” had tattoos on their hands. The tattoos garnered respect and assured the owners status for life. Polynesians developed tattoos to mark tribal communities, families, and rank. They brought their art to New Zealand and developed a facial style of tattooing called Moko which is still being used today. There is evidence that the Mayans, Incas, and Aztecs used tattooing in their rituals. Even the isolated tribes in Alaska practiced tattooing, their style indicating it was learned from the Ainu.

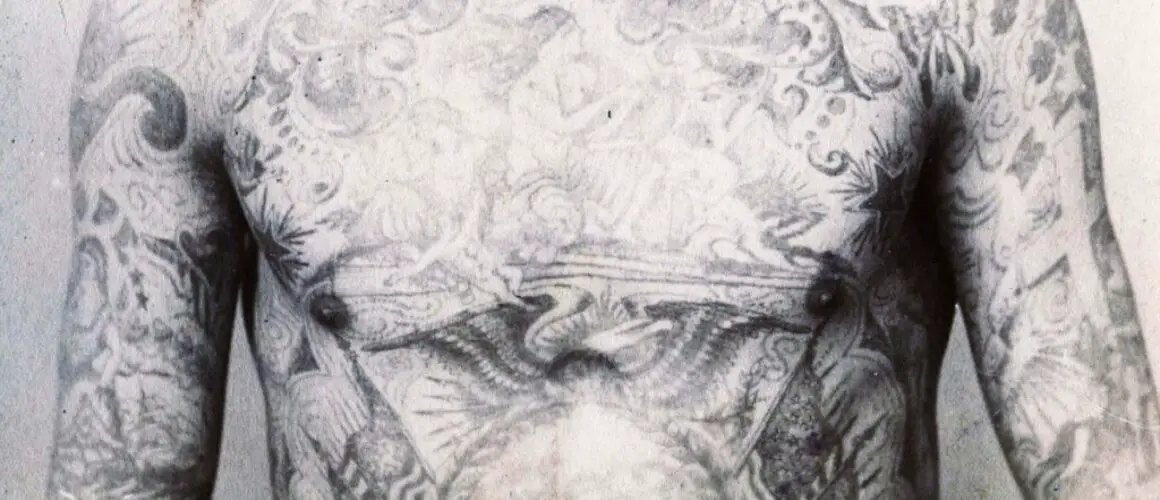

While tattooing diminished in the west, it thrived in Japan. At first, tattoos were used to mark criminals. First offenses were marked with a line across the forehead. A second crime was marked by adding an arch. A third offense was marked by another line. Together these marks formed the Japanese character for “dog”. It appears this was the original “Three strikes your out” law. In time, the Japanese escalated the tattoo into an aesthetic art form. The Japanese bodysuit originated around 1700 as a reaction to strict laws concerning conspicuous consumption. Only royalty was allowed to wear ornate clothing. As a result of this, the middle class adorned themselves with elaborate full-body tattoos. A highly tattooed person wearing only a loincloth was considered well dressed, but only in the privacy of their own home.

William Dampher is responsible for re-introducing tattooing to the west. He was a sailor and explorer who traveled the South Seas. In 1691 he brought to London a heavily tattooed Polynesian named Prince Giolo, Known as the Painted Prince. He was put on exhibition, a money-making attraction, and became the rage of London. It had been 600 years since tattoos had been seen in Europe and it would be another 100 years before tattooing would make it mark in the West.

Captain James Cook gets most of the credit for bringing tattoos to the West. In the late 1700s, he made several trips to the South Pacific. On 3rd June 1769, the passage of Venus in front of the Sun was expected and it was an event that the powerful Britannic Navy could not lose in that century of scientific explorations. The best place to observe the astronomic event was Tahiti, so Captain James Cook was sent afloat. It was not planned, but this expedition would have become one of the most important events in the history of tattooing.

Cook arrived in Tahiti months before the date and the float spent the time in Tahiti describing it as a paradise on Earth: beautiful seaside, beautiful climate and… Beautiful people. Beautiful and colorful people. Many members of the float described the men of the island covered with drawings of humans or animals – mostly birds and dogs – while the women usually had only a Z sign on every joint. Both men and women used to have other signs, too, such as concentric circles.

In fact before Cook came back from Tahiti, there was not a real word to indicate the practice of tattooing. The word came from Polynesian “tau-tau”, an onomatopoeic word that referred to the technique used in Tahiti to make tattoos. It consisted in making a comb-shaped instrument penetrate under the skin: the sound which came from it sounded like “tau-tau” and Cook reported it as “tattaow”, and then “tattaowing”. It is thought that the word was used long before Captain James Cook – approximately 150 years before – but Cook was the first to actually document the terminology during his travels. Quickly, the word has been translated into all the European languages: tattoo, tatouage, tatuaggio, tatuaje and so on. He also brought home a tattooed Polynesian guy named Omai whose overnight popularity started a short-lived tattoo fad among upper-class Londoners.

What kept tattooing from becoming more widespread was its slow and painstaking procedure. Each puncture of the skin was done by hand the ink was applied. In 1891, Samuel O’Rtiely patented the first electric tattooing machine. Based on an earlier patent by Thomas Edison designed to make copies of office documents by punching through the original and depositing ink in the second leaf of paper underneath.

This device employed an electric motor to drive a rotating crankshaft which lifted and lowered the needle. The electric tattoo machine allowed anyone to obtain a reasonably priced, and readily available tattoo. As the average person could easily get a tattoo, the upper classes turned away from it.

The cultural view of tattooing was so poor for most of the century that tattooing went underground. Few were accepted into the secret society of artists and there were no schools to study the craft. There were no magazines or associations. Tattoo suppliers rarely advertised their products. One had to learn through the scuttlebutt where to go and who to see for quality tattoos.

The birthplace of the American-style tattoo was Chatham Square in New York City. At the turn of the century, it was a seaport and entertainment center attracting working-class people with money. Samuel O’Riely came from Boston and set up shop there. He took on an apprentice named Charlie Wagner. After O’Reily’s death in 1908, Wagner opened a supply business with Lew Alberts. Alberts had trained as a wallpaper designer and he transferred those skills to the design of tattoos. He is noted for redesigning a large portion of early tattoo flash art.

While tattooing was declining in popularity across the country, Chatham Square flourished. Husbands tattooed their wives with examples of their best work. They played the role of walking advertisements for their husbands’ work. At this time, cosmetic tattooing became popular, blush for cheeks, colored lips, and eyeliner. With world war I, the flash art images changed to those of bravery and wartime icons.

In the 1920s, with prohibition and then the depression, Chatham Square lost its appeal. The center for tattoo art moved to Coney Island. Across the country, tattooists opened shops in areas that would support them, namely cities with military bases close by, particularly naval bases. Tattoos were known as travel markers. You could tell where a person had been by their tattoos.

After world war II, tattoos became further denigrated by their associations with Marlon Brando-type bikers and Juvenile delinquents. Tattooing had little respect in American culture. Then, in 1961 there was an outbreak of hepatitis and tattooing was sent reeling on its heels.

Though most tattoo shops had sterilization machines, few used them. Newspapers reported stories of blood poisoning, hepatitis, and other diseases. The general population held tattoo parlors in disrepute. At first, the New York City government gave the tattoos an opportunity to form an association and self-regulate, but tattooists are independent and they were not able to organize themselves. A health code violation went into effect and the tattoo shops at Times Square and Coney Island were shut down. For a time, it was difficult to get a tattoo in New York. It was illegal and tattoos had a terrible reputation. Few people wanted a tattoo. The better shops moved to Philadelphia and New Jersey where it was still legal.

In the late 1960s, the attitude towards tattooing changed. Much credit can be given to Lyle Tuttle, known as the “father of modern tattooing”. He tattooed celebrities, particularly women. Magazines and television went to Lyle to get information about this ancient art form.

He had seen a string of rock stars come and go in his San Francisco shop door during his glory years in the American tattoo scene—one of them being the rock lioness Janis Joplin whom Tuttle described as the “crazy gal with her hair and bracelets on.” She paid Tuttle a visit for a bracelet tattoo and a tiny heart tattoo on the breast. She was photographed with her new tattoo showing, and Lyle and other tattoo artists were flooded by demand from women for “the Janis tattoo.” That fateful meeting with Janis Joplin skyrocketed the then-young tattooer’s career in the tattoo scene, making him a household name. That was also around the time tattooing was outlawed in New York City and the time when the women’s liberation movement first made waves in America.

Today, tattooing is making a strong comeback. It is more popular and accepted than it has ever been. All classes of people seek the best tattoo artists. This rise in popularity has placed tattooists in the category of “fine artist”. The tattooist has garnered respect not seen for over 100 years. Current artists combine the tradition of tattooing with their personal style creating unique and phenomenal body art. With the addition of new inks, tattooing has certainly reached a new plateau.